Ottoman architecture

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

Ottoman architecture is an architectural style or tradition that developed under the Ottoman Empire over a long period,[1] undergoing some significant changes during its history.[2] It first emerged in northwestern Anatolia in the late 13th century[3] and developed from earlier Seljuk Turkish architecture, with influences from Byzantine and Iranian architecture along with other architectural traditions in the Middle East.[4] Early Ottoman architecture experimented with multiple building types over the course of the 13th to 15th centuries, progressively evolving into the classical Ottoman style of the 16th and 17th centuries. This style was a mixture of native Turkish tradition and influences from the Hagia Sophia, resulting in monumental mosque buildings focused around a high central dome with a varying number of semi-domes.[5][6][7] The most important architect of the classical period is Mimar Sinan, whose major works include the Şehzade Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, and Selimiye Mosque.[7][8] The second half of the 16th century also saw the apogee of certain decorative arts, most notably in the use of Iznik tiles.[9]

Beginning in the 18th century, Ottoman architecture was opened to external influences, particularly Baroque architecture in Western Europe. Changes appeared during the style of the Tulip Period, followed by the emergence of the Ottoman Baroque style in the 1740s.[10][11] The Nuruosmaniye Mosque is one of the most important examples of this period.[12][13] The architecture of the 19th century saw more influences imported from Western Europe, brought in by architects such as those from the Balyan family.[14] Empire style and Neoclassical motifs were introduced and a trend towards eclecticism was evident in many types of buildings, such as the Dolmabaçe Palace.[15] The last decades of the Ottoman Empire saw the development of a new architectural style called neo-Ottoman or Ottoman revivalism, also known as the First National Architectural Movement, by architects such as Mimar Kemaleddin and Vedat Tek.[16][14]

Ottoman dynastic patronage was concentrated in the historic capitals of Bursa, Edirne, and Istanbul (Constantinople), as well as in several other important administrative centers such as Amasya and Manisa. It was in these centers that most important developments in Ottoman architecture occurred and that the most monumental Ottoman architecture can be found.[17] Major religious monuments were typically architectural complexes, known as a külliye, that had multiple components providing different services or amenities. In addition to a mosque, these could include a madrasa, a hammam, an imaret, a sebil, a market, a caravanserai, a primary school, or others.[18] Ottoman constructions were still abundant in Anatolia and in the Balkans (Rumelia), but in the more distant Middle Eastern and North African provinces older Islamic architectural styles continued to hold strong influence and were sometimes blended with Ottoman styles.[19][20]

Early Ottoman period[edit]

Early developments[edit]

The first Ottomans were established in northwest Anatolia near the borders of the Byzantine Empire. Their position at this frontier encouraged influences from Byzantine architecture and other ancient remains in the region, and there were examples of similar architectural experimentation by the other local dynasties of the region.[21] One of the early Ottoman stylistic distinctions that emerged was a tradition of designing more complete façades in front of mosques, especially in the form of a portico with arches and columns.[21] Another early distinction was the reliance on domes.[22] The first Ottoman structures were built in Söğüt, the earliest Ottoman capital, and in nearby Bilecik, but they have not survived in their original form. They include a couple of small mosques and a mausoleum built in Ertuğrul's time (late 13th century).[23] Bursa was captured in 1326 by the Ottoman leader Orhan. It served as the Ottoman capital until 1402, becoming a major center of patronage and construction.[24] Orhan also captured İznik in 1331, turning it into another early center of Ottoman art.[25] In this early period there were generally three types of mosques: the single-domed mosque, the T-plan mosque, and the multi-unit or multi-dome mosque.[22]

Single-domed mosques[edit]

The Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333) in İznik is the oldest Ottoman mosque with an inscription that documents its construction.[21] It is also the first example of an Ottoman single-domed mosque, consisting of a square chamber covered by a dome.[26] It is built in alternating layers of brick and cut stone, a technique which was likely copied from Byzantine examples and recurred in other Ottoman structures.[27] The dome is covered in terracotta tiles, which was also a custom of early Ottoman architecture before later Ottoman domes were covered in lead.[27] Other structures from the time of Orhan were built at İznik, Bilecik, and in Bursa.[28] Single-domed mosques continued to be built after this, such as the example of the Green Mosque in Iznik (1378–1391), which was built by an Ottoman pasha. The Green Mosque of İznik is the first Ottoman mosque for which the name of the architect (Hacı bin Musa) is known.[29] The main dome covers a square space, and as a result the transition between the round base of the dome and the square chamber below is achieved through a series of triangular carvings known as "Turkish triangles", a type of pendentive which was common in Anatolian Seljuk and early Ottoman architecture.[18][30][31] An example of a single-domed mosque with a much larger dome can be found in the Yildirim Bayezid I Mosque in Mudurnu, which dates from around 1389. The ambitious dome, with a diameter of 20 meters, was comparable to much later Ottoman mosques but it had to be built closer to the ground in order to be stable. Instead of Turkish triangles the transition is made through squinches that start low along the walls.[32]

- Single-domed mosques

-

Hacı Özbek Mosque in Iznik (1333), one of the earliest surviving Ottoman mosques

-

Green Mosque in Iznik (1378–1391)

-

Green Mosque interior: "Turkish triangles" form the transition from dome to square chamber[30]

-

Interior of Yildirim Bayezid Mosque in Mudurnu (circa 1389)

"T-plan" mosques or zaviyes[edit]

In 1334–1335 Orhan built a mosque outside the Yenişehir Gate in İznik which no longer stands but has been excavated and studied by archeologists. It is significant as the earliest known example of a type of building called a zaviye (a cognate of Arabic zawiya), "T-plan" mosque, or "Bursa-type" mosque.[33] This type of building is characterized by a central courtyard, typically covered by a dome, with iwans (domed or vaulted halls that are open to the courtyard) on three sides, one of which is oriented towards the qibla (direction of prayer) and contains the mihrab (wall niche symbolizing the qibla). The front façade usually incorporated a portico along its entire width. The iwans on the side and the other various rooms attached to these buildings may have served to house Sufi students and traveling dervishes, since the Sufi brotherhoods were one of the main supporters of the early Ottomans.[34] Variations of this floor plan were the most common type of major religious structure sponsored by the early Ottoman elites. The "Bursa-type" label comes from the fact that multiple examples of this kind were built in and around Bursa, including the Orhan Gazi Mosque (1339), the Hüdavendigar (Murad I) Mosque (1366–1385), the Yildirim Bayezid I Mosque (completed in 1395), and the Green Mosque built by Mehmed I.[35][28][18] The Green Mosque, begun in 1412 and completed in 1424,[36] is notable for its extensive tile decoration in the cuerda seca technique. It is the first instance of lavish tile decoration in Ottoman architecture.[36] These mosques were all part of larger religious complexes (külliyes) that included other structures offering services such as madrasas (Islamic colleges), hammams (public bathhouses), and imarets (charitable kitchens).[18]

Notable examples of T-plan buildings beyond Bursa include the Firuz Bey Mosque in Milas, built in 1394 by a local Ottoman governor,[37][38] and the Nilüfer Hatun Imaret in Iznik, originally a zaviye built in 1388 to honor Murad I's mother.[39] The Firuz Bey Mosque is notable for being built in stone and featuring carved decoration of high quality.[37][40] Two other T-plan examples, the Beylerbeyi Mosque in Edirne (1428–1429) and the Yahşi Bey Mosque in Izmir (circa 1441–1442), are both significant as later T-plan structures with more complex decorative roof systems. In both buildings the usual side iwans are replaced by separate halls accessed through doorways from the central space. As a result, prayers were probably only held in the qibla-oriented iwan, demonstrating how zaviye buildings were often not designed as simple mosques but had more complex functions instead. In both buildings the qibla iwan is semi-octagonal in shape and is covered by a semi-dome. Large muqarnas carvings, grooving, or other geometrical carvings decorate the domes and semi-domes.[41]

- T-plan mosques and buildings

-

Orhan Gazi Mosque in Bursa (1339): exterior and front portico

-

Orhan Gazi Mosque: interior prayer hall, view towards the qibla

-

Hüdavendigar Mosque in Bursa (1366–1385): interior of the prayer hall

-

Nilüfer Hatun Imaret in Iznik (1388)

-

Yıldırım Bayezid I Mosque in Bursa (1395): exterior and portico

-

Yıldırım Bayezid I Mosque: interior view towards the qibla iwan

-

Firuz Bey Mosque in Milas (1394): exterior façade

-

Green Mosque in Bursa (1412–1424): exterior façade and entrance portal

-

Green Mosque: interior

-

Green Mosque: mihrab and tile decoration

-

Green Tomb in Bursa (1412–24), part of the Green Mosque complex

-

Interior of the Green Tomb

-

Beylerbeyi Mosque in Edirne (1428–1429): interior view of the qibla iwan

Multi-dome buildings[edit]

The most unusual mosque of this period is the congregational mosque known as the Grand Mosque of Bursa or Ulu Cami. The mosque was commissioned by Bayezid I and funded by the booty from his victory at the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396. It was finished a few years later in 1399–1400.[42] It is a multi-dome mosque, consisting of a large hypostyle hall divided into twenty equal bays in a rectangular four-by-five grid, each covered by a dome supported by stone piers. The dome over the middle bay of the second row has an oculus and its floor is occupied by a fountain, serving a role similar to the sahn (courtyard) in the mosques of other regions.[42] The minbar (pulpit) of the mosque is among the finest examples of early Ottoman wooden minbars made with the kündekari technique, in which pieces of wood are fitted together without nails or glue. Its surfaces are decorated with inscriptions, floral (arabesque) motifs, and geometric motifs.[43]

After Bayezid I suffered a disastrous defeat in 1402 at the Battle of Ankara against Timur, the capital was moved to Edirne in Thrace. Another multi-dome congregational mosque was begun here by Suleyman Çelebi in 1403 and finished by Mehmed I in 1414. It is known today as the Old Mosque (Eski Cami). It is slightly smaller than the Bursa Grand Mosque, consisting of a square floor plan divided into nine domed bays supported by four piers.[42][44] This was the last major multi-dome mosque built by the Ottomans (with some exceptions such as the later Piyale Pasha Mosque). In later periods, the multi-dome building type was adapted for use in non-religious buildings instead.[45] One example of this is the bedesten – a kind of market hall at the center of a bazaar – which Bayezid I built in Bursa during his reign.[46] A similar bedesten was built in Edirne by Mehmed I between 1413 and 1421.[46]

- Multi-domed mosques and buildings

-

Grand Mosque of Bursa (1396–1400)

-

Interior of the Grand Mosque of Bursa

-

Wooden minbar of the Grand Mosque of Bursa

-

Old Mosque of Edirne (1403–1414)

-

Interior of the Old Mosque of Edirne

-

Interior of the Bedesten of Bursa (with modern-day shops)

-

Exterior view of the Bedesten of Edirne

-

Koca Mahmut Paşa Camii (build 1451-1494), Sofia

Murad II and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque[edit]

The period of Murad II (between 1421 and 1451) saw the continuation of some traditions and the introduction of new innovations. Although the capital was at Edirne, Murad II had his funerary complex (the Muradiye Complex) built in Bursa between 1424 and 1426.[47] It included a mosque (heavily restored in the 19th century), a madrasa, an imaret, and a mausoleum. Its cemetery developed into a royal necropolis when later mausoleums were built here, although Murad II was the only sultan buried here.[48][49] Murad II's mausoleum is unique among royal Ottoman tombs as its central dome has an opening to the sky and his son's mausoleum was built directly adjacent to it, as per the sultan's last wishes.[48][50] The madrasa of the complex is one of the most architecturally accomplished of this period and one of the few of its kind from this period to survive.[48][51] It has a square courtyard with a central fountain (shadirvan) surrounded by a domed portico, behind which are vaulted rooms. On the southeast side of the courtyard is a large domed classroom (dershane), whose entrance façade (facing the courtyard) features some tile decoration.[48] In Edirne Murad II built another zaviye for Sufis in 1435, now known as the Murad II Mosque. It repeats the Bursa-type plan and also features rich tile decoration similar to the Green Mosque in Bursa, as well as new blue-and-white tiles with Chinese influences.[52][53]

The most important mosque of this period is the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, begun by Murad II in 1437 and finished in 1447.[54][55] It has a very different design from earlier mosques. The floor plan is nearly square but is divided between a rectangular courtyard and a rectangular prayer hall. The courtyard has a central fountain and is surrounded by a portico of arches and domes, with a decorated central portal leading into the courtyard from the outside and another one leading from the courtyard into the prayer hall. The prayer hall is centered around a huge dome which covers most of the middle part of the hall, while the sides of the hall are covered by pairs of smaller domes. The central dome, 24 meters in diameter (or 27 meters according to Kuban[56]), is much larger than any other Ottoman dome built before this.[57] On the outside, this results in an early example of the "cascade of domes" visual effect seen in later Ottoman mosques, although the overall arrangement here is described by Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom as not yet successful compared to later examples.[54] The mosque has a total of four minarets, arranged around the four corners of the courtyard. Its southwestern minaret was the tallest Ottoman minaret built up to that time and features three balconies, from which the mosque's name derives.[58]

The overall form of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, with its central-dome prayer hall, arcaded court with fountain, minarets, and tall entrance portals, foreshadowed the features of later Ottoman mosque architecture.[54] It has been described as a "crossroads of Ottoman architecture",[54] marking the culmination of architectural experimentation with different spatial arrangements during the period of the Beyliks and the early Ottomans.[54][55][57] Kuban describes it as the "last stage in Early Ottoman architecture", while the central dome plan and the "modular" character of its design signaled the direction of future Ottoman architecture in Istanbul.[59]

- Complexes of Murad II

-

Tomb of Murad II at the Muradiye Complex in Bursa (circa 1426)

-

Entrance to the Murad II Medrese in Bursa (circa 1426)

-

Remains of tile and fresco decoration in the Murad II Mosque in Edirne (circa 1435)

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne (1437–1447): exterior

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque: courtyard

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque: interior

Mehmed II and early Ottoman Istanbul[edit]

Mehmed II succeeded his father temporarily in 1444 and definitively in 1451. He is also known as "Fatih" or the Conqueror after his conquest of Constantinople in 1453, which brought the remains of the Byzantine Empire to an end. Mehmed was strongly interested in Turkish, Persian, and European cultures and sponsored artists and writers at his court.[60] Before the 1453 conquest his capital remained at Edirne, where he completed a new palace for himself in 1452–53.[60] He made extensive preparations for the siege, including the construction of a large fortress known as Rumeli Hisarı on the western shore of the Bosphorus, begun in 1451-52 and completed shortly before the siege in 1453.[61] This was located across from an older fortress on the eastern shore known as Anadolu Hisarı, built by Bayezid I in the 1390s for an earlier siege, and was designed to cut off communications to the city through the Bosphorus.[62] Rumeli Hisarı remains one of the most impressive medieval Ottoman fortifications. It consists of three large round towers connected by curtain walls, with an irregular layout adapted to the topography of the site. A small mosque was built inside the fortified enclosure. The towers once had conical roofs, but these disappeared in the 19th century.[61]

After the conquest of Constantinople (now known as Istanbul), one of Mehmed's first constructions in the city was a palace, known as the Old Palace (Eski Saray), built in 1455 on the site of what is now the main campus of Istanbul University.[60] At the same time Mehmed built another fortress, Yedikule ("Seven Towers"), at the south end of the city's land walls in order to house and protect the treasury. It was completed in 1457–1458. Unlike Rumeli Hisarı, it has a regular layout in the shape of a five-pointed star, possibly of Italian inspiration.[63][60] In order to revitalize commerce, Mehmed built the first bedesten in Istanbul between 1456 and 1461, variously known as the Inner Bedesten (Iç Bedesten), Old Bedesten (Eski Bedesten or Bedesten-i Atik), or the Jewellers' Bedesten (Cevahir Bedesteni).[64][65] A second bedesten, the Sandal Bedesten, also known as the Small Bedesten (Küçük Bedesten) or New Bedesten (Bedesten-i Cedid), was built by Mehmed about a dozen years later.[64][66] These two bedestens, each consisting of a large multi-dome hall, form the original core of what is now the Grand Bazaar, which grew around them over the following generations.[64][66] The nearby Tahtakale Hammam, the oldest hammam (public bathhouse) of the city, also dates from around this time.[67] The only other documented hammams in the city which date from the time of Mehmet II are the Mahmut Pasha Hamam (part of the Mahmut Pasha Mosque's complex) built in 1466[67][68] and the Gedik Ahmet Pasha Hamam built around 1475.[62]

- Early Ottoman buildings in Istanbul under Mehmed II

-

Yedikule Fortress in Istanbul (circa 1458)

-

Interior of the Sandal Bedesten in the Grand Bazaar, Istanbul

-

Interior of the Tahtakale Hamam (dome is original but the balconies are modern)

-

Mahmut Pasha Hamam, Istanbul (1466)

-

Mahmut Pasha Hamam: dome interior

In 1459 Mehmed II began construction of a second palace, known as the New Palace (Yeni Saray) and later as the Topkapi Palace ("Cannon-Gate Palace"), on the site of the former acropolis of Byzantium, a hill overlooking the Bosphorus.[69] The palace was mostly laid out between 1459 and 1465.[62] Initially it remained mostly an administrative palace, while the residence of the sultan remained at the Old Palace. It only became a royal residence in the 16th century, when the harem section was constructed.[62] The palace has been repeatedly modified over subsequent centuries by different rulers, with the palace today now representing an accumulation of different styles and periods. Its overall layout appears highly irregular, consisting of several courtyards and enclosures within a precinct delimited by an outer wall. The seemingly irregular layout of the palace was in fact a reflection of a clear hierarchical organization of functions and private residences, with the innermost areas reserved for the privacy of the sultan and his innermost circle.[69] Among the structures today that date from Mehmet's time is the Fatih Kiosk or Pavilion of Mehmed II, located on the east side of the Third Court and built in 1462–1463.[70] It consists of a series of domed chambers preceded by an arcaded portico on the palace-facing side. It stands on top of a heavy substructure built into the hillside overlooking the Bosphorus. This lower level also originally served as a treasury. The presence of strongly-built foundation walls and substructures like this was a common characteristic of Ottoman construction in this palace as well as other architectural complexes.[71] Bab-ı Hümayun, the main outer entrance to the palace grounds, dates from Mehmet II's time according to an inscription that gives the date 1478–1479, but it was covered in new marble during the 19th century.[72][73] Kuban also argues that the Babüsselam (Gate of Salution), the gate to the Second Court flanked by two towers, dates to the time Mehmed II.[74] Within the outer gardens of the palace, Mehmed II commissioned three pavilions built in three different styles. One pavilion was in Ottoman style, another in Greek style, and a third one in a Persian style.[69][73] Of these, only the Persian pavilion, known as the Tiled Kiosk (Çinili Köşk), has survived. It was completed in September or October 1472 and its name derives from its rich tile decoration, including the first appearance of Iranian-inspired banna'i tilework in Istanbul. The vaulting and cruciform layout of the building's interior is also based on Iranian precedents, while the exterior is fronted by a tall portico. Although not much is known about the builders, they were likely of Iranian origin, as historical documents indicate the presence of tilecutters from Khorasan.[69]

- Palace architecture of Mehmed II

-

Bab-ı Hümayun, the outer gate to the Topkapi Palace (1478–1479, with later renovations)

-

Babüsselam, the gate to the Second Court in Topkapi Palace

-

Fatih Kiosk in the Third Court of Topkapi Palace (1462–1463)

-

Tiled Kiosk in the outer gardens of Topkapi Palace (1472)

-

Tile decoration of the Tiled Kiosk

Mehmed's largest contribution to religious architecture was the Fatih Mosque complex in Istanbul, built from 1463 to 1470. It was part of a very large külliye which also included a tabhane (guesthouse for travelers), an imaret, a darüşşifa (hospital), a caravanserai (hostel for traveling merchants), a mektep (primary school), a library, a hammam, shops, a cemetery with the founder's mausoleum, and eight madrasas along with their annexes.[75][62] Not all of these structures have survived to the present day. The buildings largely ignored any existing topography and were arranged in a strongly symmetrical layout on a vast square terrace with the monumental mosque at its center.[76] The architect of the mosque complex was Usta Sinan, known as Sinan the Elder.[77] It was located on the Fourth Hill of Istanbul, which was until then occupied by the ruined Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles.[77] Unfortunately, much of the mosque was destroyed by an earthquake in 1766, causing it to be largely rebuilt by Mustafa III in a significantly altered form shortly afterwards. Only the walls and porticos of the mosque's courtyard and the marble entrance to the prayer hall have survived overall from the original mosque.[78][79][80] The form of the rest of the mosque has had to be reconstructed by scholars using historical sources and illustrations.[77][80] The design likely reflected the combination of the Byzantine church tradition (especially the Hagia Sophia) with the Ottoman tradition that had evolved since the early imperial mosques of Bursa and Edirne.[76][81] Drawing on the ideas established by the earlier Üç Şerefeli Mosque, the mosque consisted of a rectangular courtyard with a surrounding gallery leading to a domed prayer hall. The prayer hall consisted of a large central dome with a semi-dome behind it (on the qibla side) and flanked by a row of three smaller domes on either side.[76]

The reign of Bayezid II[edit]

After Mehmed II, the reign of Bayezid II (1481–1512) is again marked by extensive architectural patronage, of which the two most outstanding and influential examples are the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne and the Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul.[82] While it was a period of further experimentation, the Mosque of Bayezid II in Amasya, completed in 1486, was still based on the Bursa-type plan, representing the last and largest imperial mosque in this style.[7] Doğan Kuban regards the constructions of Bayzezid II as also constituting deliberate attempts at urban planning, extending the legacy of the Fatih Mosque complex in Istanbul.[83]

The Bayezid II Complex in Edirne is a complex (külliye) of buildings including a mosque, a darüşşifa, an imaret, a madrasa, a tımarhane (asylum for the mentally ill), two tabhanes, a bakery, latrines, and other services, all linked together on the same site. It was commissioned by Bayezid II in 1484 and completed in 1488 under the direction of the architect Hayrettin.[84][85] The various structures of the complex have relatively simple but strictly geometrical floor plans, built of stone with lead-covered roofs, with only sparse decoration in the form of alternating coloured stone around windows and arches.[86][7] This has been described as an "Ottoman classical architectural aesthetic at an early stage in its development".[7] The mosque lies at the heart of the complex. It has an austere square prayer hall covered by a large high dome. The hall is preceded by a rectangular courtyard with a fountain and a surrounding arcade. The darüşşifa, whose function was the main motivation behind Bayezid's construction of the complex, has two inner courtyards that lead to a structure with a hexagonal floor plan featuring small domed rooms arranged around a larger central dome.[87]

The Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul was built between 1500 and 1505 under the direction of the architect Ya'qub or Yakubshah (although Hayrettin is also mentioned in documents).[88][7][89] It too was part of a larger complex, which included a madrasa (serving today as a Museum of Turkish Calligraphy Art), a monumental hammam (the Bayezid II Hamam), hospices, an imaret, a caravanserai, and a cemetery around the sultan's mausoleum.[90][91] The mosque itself, the largest building, once again consists of a courtyard leading to the square prayer hall. However, the prayer hall now makes use of two semi-domes aligned with the main central dome, while the side aisles are each covered by four smaller domes. Compared to earlier mosques, this results in a much more sophisticated "cascade of domes" effect for the building's exterior profile, likely reflecting influences from the Hagia Sophia and the original (now disappeared) Fatih Mosque.[92] The mosque is the culmination of this period of architectural exploration under Bayezid II and the last step towards the classical Ottoman style.[93][94] The deliberate arrangement of established Ottoman architectural elements into a strongly symmetrical design is one aspect which denotes this evolution.[94]

- Complexes of Bayezid II

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Amasya (1486)

-

Bayezid II Complex in Edirne (1484–1488)

-

Interior of the mosque at the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne

-

Inner courtyard of the darüşşifa at the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul (1500–1505)

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul: dome interiors

-

Bayezid II Hamam, part of the Bayezid II complex in Istanbul

Classical period[edit]

The start of the classical period is strongly associated with the works of the imperial architect Mimar Sinan.[95][96] During this period the bureaucracy of the Ottoman state, whose foundations were laid in Istanbul by Mehmet II, became increasingly elaborate and the profession of the architect became further institutionalized.[7] The long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is also recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.[7] In this period Ottoman architecture, especially under the work and influence of Sinan, saw a new unification and harmonization of the various architectural elements and influences that Ottoman architecture had previously absorbed but which had not yet been harmonized into a collective whole.[95] Ottoman architecture used a limited set of general forms – such as domes, semi-domes, and arcaded porticos – which were repeated in every structure and could be combined in a limited number of ways.[60] The ingenuity of successful architects such as Sinan lay in the careful and calculated attempts to solve problems of space, proportion, and harmony.[60] This period is also notable for the development of Iznik tile decoration in Ottoman monuments, with the artistic peak of this medium beginning in the second half of the 16th century.[97][98]

The era of Sinan[edit]

The master architect of the classical period, Mimar Sinan, served as the chief court architect (mimarbaşi) for some 50 years from 1538 until his death in 1588.[99] Sinan credited himself with the design of over 300 buildings,[100] though another estimate of his works puts it at nearly 500.[101] He is credited with designing buildings as far as Buda (present-day Budapest) and Mecca.[102] He was probably not present to directly supervise projects far from the capital, so in these cases his designs were most likely executed by his assistants or by local architects.[103][104]

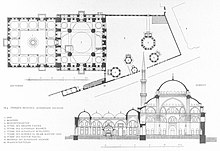

Sinan's first major imperial commission was the Şehzade Mosque complex, which Suleiman dedicated to Şehzade Mehmed, his son who died in 1543.[105] The complex was built between 1545 and 1548.[92] The mosque has a rectangular floor plan divided into two equal squares, with one square occupied by the courtyard and the other occupied by the prayer hall.[92] The prayer hall consists of a central dome surrounded by semi-domes on four sides, with smaller domes occupying the corners. Smaller semi-domes also fill the space between the corner domes and the main semi-domes. This design represents the culmination of the previous domed and semi-domed buildings in Ottoman architecture, bringing complete symmetry to the dome layout.[106] Sinan's early innovations are also evident in the way he organized the structural supports of the dome. Instead of having the dome rest on thick walls all around it (as was previously common), he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of buttresses along the outer walls of the mosque and in four pillars inside the mosque itself at the corners of the dome. This allowed for the walls in between the buttresses to be thinner, which in turn allowed for more windows to bring in more light.[107] Sinan also moved the outer walls inward, near the inner edge of the buttresses, so that the latter were less visible inside the mosque.[107] On the outside, he added domed porticos along the lateral façades of the building which further obscured the buttresses and gave the exterior a greater sense of monumentality.[107][108]

The basic design of the Şehzade Mosque, with its symmetrical dome and four semi-dome layout, proved popular with later architects and was repeated in classical Ottoman mosques after Sinan (e.g. the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, the New Mosque at Eminönü, and the 18th-century reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque).[109][110] Despite this legacy and the symmetry of its design, Sinan considered the Sehzade Mosque his "apprentice" work and was not satisfied with it.[92][111][112] During the rest of his career he did not repeat its layout in any of his other works. He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque. One of the results of this logic was that any space that did not belong the central domed space was reduced to a minimum, subordinate role, if not altogether absent.[113]

In 1550, Sinan began construction for the Süleymaniye complex, a monumental religious and charitable complex dedicated to Suleiman. Construction finished in 1557. Following the example of the earlier Fatih complex, it consists of many buildings arranged around the main mosque in the center, on a planned site occupying the summit of a hill in Istanbul.[114][115] The Süleymaniye Mosque complex is one of the most important symbols of Ottoman architecture and is often considered by scholars to be the most magnificent mosque in Istanbul.[116][117][22][118] The mosque itself has a form similar to that of the earlier Bayezid II Mosque: a central dome preceded and followed by semi-domes, with smaller domes covering the sides.[119] In particular, the building replicates the central dome layout of the Hagia Sophia and this may be interpreted as a desire by Suleiman to emulate the structure of the Hagia Sophia, demonstrating how this ancient monument continued to hold tremendous symbolic power in Ottoman culture.[119] Nonetheless, Sinan employed innovations similar to those he used previously in the Şehzade Mosque: he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of columns and pillars, which allowed for more windows in the walls and minimized the physical separations within the interior of the prayer hall.[120][121] The exterior façades of the mosque are characterized by ground-level porticos, wide arches in which sets of windows are framed, and domes and semi-domes that progressively culminate upwards – in a roughly pyramidal fashion – to the large central dome.[120][122]

After designing the Süleymaniye complex, Sinan appears to have focused on experimenting with the single-domed space.[113] In the 1550s and 1560s, he experimented with an "octagonal baldaquin" design for the main dome, in which the dome rests on an octagonal drum supported by a system of eight pillars or buttresses. An example of this is the Rüstem Pasha Mosque (1561) in Istanbul.[123] This mosque is also famous for its wide array of Iznik tiles covering the walls of its exterior portico and its interior, unprecedented in Ottoman architecture,[124] contrasting with the usually restrained decoration Sinan employed in other buildings.[97]

Sinan's crowning masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, which was begun in 1568 and completed in 1574 (or possibly 1575).[125][126] Its prayer hall is notable for being completely dominated by a single massive dome, whose view is unimpeded by the structural elements seen in other large domed mosques before this.[127] This design is the culmination of Sinan's spatial experiments, making use of the octagonal baldaquin as the most effective method of integrating the round dome with the rectangular hall below by minimizing the space occupied by the supporting elements of the dome.[128][129] The dome is supported on eight massive pillars which are partly freestanding but closely integrated with the outer walls. Additional outer buttresses are concealed in the walls of the mosque, allowing the walls in between to be pierced with a large number of windows.[130] Sinan's biographies praise the dome for its size and height, which is approximately the same diameter as the Hagia Sophia's main dome and slightly higher; the first time that this had been achieved in Ottoman architecture.[130]

After Sinan[edit]

After Sinan, the classical style became less creative and more repetitive by comparison with earlier periods.[60] Davud Agha succeeded Sinan as chief architect. Among his most notable works, all in Istanbul, are the Cerrahpaşa Mosque (1593), the Koca Sinan Pasha Complex on Divanyolu (1593), the Gazanfer Ağa Medrese complex (1596), and the Tomb of Murad III (completed in 1599).[62][131][132] Some scholars argue that the Nışançı Mehmed Pasha Mosque (1584–1589), whose architect is unknown, should be attributed to him.[133][134][135] Its design is considered highly accomplished and it may be one of the first Ottoman mosques to be fronted by a garden courtyard.[135][134][62] Davud Agha was one of the few architects of this period to display great potential and to create designs that went beyond Sinan's designs, but unfortunately he died of the plague right before the end of the 16th century.[136]

The Sultan Ahmed I Mosque was begun in 1609 and completed in 1617.[137] It was designed by Sinan's apprentice, Mehmed Agha.[138] The mosque's size, location, and decoration suggest it was intended to be a rival to the nearby Hagia Sophia.[139] Its design essentially repeats that of the Şehzade Mosque.[140] On the outside, Mehmed Agha opted to achieve a "softer" profile with the cascade of domes and the various curving elements, differing from the more dramatic juxtaposition of domes and vertical elements seen in earlier classical mosques by Sinan.[141][142] It is also the only Ottoman mosque to have as many as six minarets.[118] On the inside, the mosque's lower walls are lavishly decorated with thousands of predominantly blue Iznik tiles; along with the painted decoration on the rest of the walls, this has given the mosque its popular name, the Blue Mosque.[143] After the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, no further great imperial mosques dedicated to a sultan were built in Istanbul until the mid-18th century. Mosques continued to be built and dedicated to other dynastic family members, but the tradition of sultans building their own monumental mosques lapsed.[144]

Some of the best examples of early 17th-century Ottoman architecture are the Revan Kiosk (1635) and Baghdad Kiosk (1639) in Topkapı Palace, built by Murad IV to commemorate his victories against the Safavids.[145] Both are small pavilions raised on platforms overlooking the palace gardens. Both are harmoniously decorated on the inside and outside with predominantly blue and white tiles and richly-inlaid window shutters.[145]

Tulip Period (early 18th century)[edit]

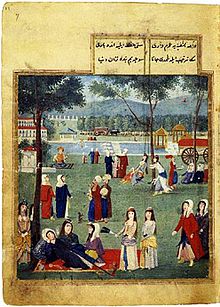

The historical period known as the Tulip Period or Tulip Era is considered to have begun in 1718, during Ahmed III's reign (r. 1703–1730), and lasted until the Patrona Halil revolts of 1730, when Ahmed III was overthrown. These years of peace inaugurated a new era of growing cross-cultural exchange between the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe.[147] From the 18th century onward, European influences were introduced into Ottoman architecture as the Ottoman Empire itself became more open to outside influences. The term "Baroque" is sometimes applied more widely to Ottoman art and architecture across the 18th century including the Tulip Period.[148][118] In more specific terms, however, the period after the 17th century is marked by several different styles.[149][18] Ünver Rüstem states that constructions from the first years of Ahmed III's reign (after 1703) demonstrate that the new "Tulip Period" style was already in existence by then.[150] The period saw significant influence from the French Rococo style (part of the wider Baroque style) that emerged around this time under the reign of Louis XV.[151] In 1720, an Ottoman embassy led by Yirmisekiz Çelebi Mehmed Efendi was sent to Paris and when it returned in 1721 it brought back reports and illustrations of the French Baroque style which made a strong impression in the sultan's court.[152][118][151][153] In addition to European influences, the decoration of the Tulip Period was also influenced by Safavid art and architecture to the east.[154][155]

One of the most important creations of the Tulip Period was the Sadâbâd Palace, a new summer palace designed and built by Damat Ibrahim Pasha in 1722–1723 for Ahmed III.[156][157] It was located at Kâğıthane, a rural area on the outskirts of the city with small rivers that flow into the Golden Horn inlet. The palace grounds included a long marble-lined canal, the Cedval-i Sim, around which were gardens, pavilions, and palace apartments in a landscaped setting. This overall design probably emulated French pleasure palaces as a result of Yirmisekiz's reports about Paris and Versailles.[152][158] The regular inhabitants of Istanbul also used the surrounding area as a recreational ground for excursions and picnics.[157] This was a new practice in Ottoman culture that brought the public within close proximity of the ruler's abode for the first time.[157]

The culmination of the Tulip Period style is represented by a series of monumental stand-alone fountains that were mostly built between 1728 and 1732.[159][160] Water took on an enlarged role in architecture and the urban landscape of Istanbul during the Tulip Period. In the first half of the 18th century Istanbul's water supply infrastructure, including the aqueducts in Belgrade Forest, were renovated and expanded. In 1732 an important water distribution structure, the taksim, was first built on what is now Taksim Square.[161] The new fountains were unprecedented in Ottoman architecture. Previously, fountains and sebils only existed as minor elements of larger charitable complexes or as shadirvans inside mosque courtyards. The maidan fountain, or a stand-alone fountain at the center of a city square, was introduced for the first time in this period.[162] The first and most remarkable of these is the Ahmed III Fountain built in 1728 next to the Hagia Sophia and in front of the outer gate of Topkapı Palace.[159][163]

The construction of stand-alone library structures was another new trend influenced by European ideas, as the Ottomans traditionally did not build libraries except as secondary elements attached to religious complexes. The earlier Köprülü Library, built in 1678 was the first of its kind, but other early examples date from the reign of Ahmed III during the Tulip Period.[165]

The last major monument of the Tulip Period stage in Ottoman architecture is the Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque complex completed in 1734–1735 and sponsored by the grand vizier of the same name.[166][167][168] This mosque reflects an overall classical form but the flexible placement of the various components of the complex around a garden enclosure is more reflective of the new changes in tastes. For example, the main gate of the complex is topped by a library, a feature which would have been unusual in earlier periods. It also has a very ornate sebil positioned at the street corner, next to the founder's tomb. The interior of the mosque is light and decorated with tiles from the Tekfursaray kilns, which were of lesser quality than those of the earlier Iznik period. One group of tiles is painted with an illustration of the Great Mosque of Mecca, a decorative feature of which there were multiple examples in this period.[166]

Baroque period (18th century to early 19th century)[edit]

During the 1740s a new Ottoman or Turkish "Baroque" style emerged in its full expression and rapidly replaced the style of the Tulip Period.[169][149] This shift signaled the final end to the classical style.[170] The political and cultural conditions which led to the Ottoman Baroque trace their origins in part to the Tulip Period, when the Ottoman ruling class opened itself to Western influence.[149][171] After the Tulip Period, Ottoman architecture openly imitated European architecture, so that architectural and decorative trends in Europe were often mirrored in the Ottoman Empire at the same time or after a short delay.[172] Changes were especially evident in the ornamentation and details of new buildings rather than in their overall forms, though new building types were eventually introduced from European influences as well.[118] The term "Turkish Rococo", or simply "Rococo",[170][28] is also used to describe the Ottoman Baroque, or parts of it, due to the similarities and influences from the French Rococo style in particular, but this terminology varies from author to author.[173]

The first structures to exhibit the new Baroque style are several fountains and sebils built by elite patrons in Istanbul in 1741–1742.[175] The most important monument heralding the new Ottoman Baroque style is the Nuruosmaniye Mosque complex, begun by Mahmud I in October 1748 and completed by his successor, Osman III (to whom it is dedicated), in December 1755.[176] Kuban describes it as the "most important monumental construction after the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne", marking the integration of European culture into Ottoman architecture and the rejection of the classical Ottoman style.[13] It also marked the first time since the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque (early 17th century) that an Ottoman sultan built his own imperial mosque complex in Istanbul, thus inaugurating the return of this tradition.[177]

The Ayazma Mosque in Üsküdar was built between 1757–8 and 1760–1.[178][179] It is essentially a smaller version of the Nuruosmaniye Mosque, signaling the importance of the latter as a new model to emulate.[180] Although smaller, it is relatively tall for its proportions, enhancing its sense of height. This trend towards height was pursued in later mosques.[181]

In Topkapı Palace, the Ottoman sultans and their family continued to build new rooms or remodel old ones throughout the 18th century, introducing Baroque and Rococo decoration in the process. Some examples include the Baths of the Harem section, probably renovated by Mahmud I around 1744,[182][183][184][185] As in the preceding centuries, other palaces were built around Istanbul by the sultan and his family. Previously, the traditional Ottoman palace configuration consisted of different buildings or pavilions arranged in a group, as was the case at Topkapı Palace, the Edirne Palace, and others.[186] However, at some time during the 18th century there was a transition to palaces consisting of a single block or single large building.[187]

Beyond Istanbul, the greatest palaces were built by powerful local families, but they were often built in regional styles that did not follow the trends of the Ottoman capital.[188] The Azm Palace in Damascus, for example, was built around 1750 in a largely Damascene style.[188][189] In eastern Anatolia, near present-day Doğubayazıt, the Ishak Pasha Palace is an exceptional and flamboyant piece of architecture that mixes various local traditions including Seljuk Turkish, Armenian, and Georgian. It was begun in the 17th century and generally completed by 1784.[190][191][192]

The Nusretiye Mosque, Mahmud II's imperial mosque, was built between 1822 and 1826 at Tophane.[193][194] The mosque is the first major imperial work by Krikor Balyan.[193][195] It is sometimes described as belonging to the Empire style, but is considered by Godfrey Goodwin and Doğan Kuban as one of the last Baroque mosques,[193][196] while Ünver Rüstem describes the style as moving away from the Baroque and towards an Ottoman interpretation of Neoclassicism.[195] Goodwin also describes it as the last in a line of imperial mosques that started with the Nuruosmaniye.[193] Despite its relatively small size the mosque's tall proportions creates a sense of height, which may the culmination of a trend that began with the Ayazma Mosque.[197]

19th-century and early 20th-century[edit]

During the reign of Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) the Empire style, a Neoclassical style which originated in France under Napoleon, was introduced into Ottoman architecture.[198] This marked a trend towards increasingly direct imitation of Western styles, particularly from France.[199] The Tanzimat reforms that began in 1839 under Abdülmecid I sought to modernize the Ottoman Empire with Western-style reforms. In the architectural realm, this resulted in the dominance of European architects and Ottoman architects with European training.[200] Among these, the Balyans, an Ottoman Armenian family, succeeded in dominating imperial architecture for much of the century. They were joined by European architects such as the Fossati brothers, William James Smith, and Alexandre Vallaury.[201][202] After the early 19th century, Ottoman architecture was characterized by an eclectic architecture which mixed or borrowed from multiple styles. The Balyans, for example, commonly combined Neoclassical or Beaux-arts architecture with highly eclectic decoration.[15] As more Europeans arrived in Istanbul, the neighbourhoods of Galata and Beyoğlu (or Pera) took on very European appearances.[203]

A number of mosques built in the 19th century reflect these trends, such as the Ortaköy Mosque[205][206] and the Pertevniyal Valide Mosque in Istanbul.[207][208] The Tanzimat reforms also granted Christians and Jews the right to freely build new centers of worship, which resulted in new constructions, renovations, and expansions of churches and synagogues. Most of these followed the same eclecticism that prevailed in the rest of Ottoman architecture of the 19th century.[209]

Many palaces, residences, and leisure pavilions were built in the 19th century, most of them in the Bosphorus suburbs of Istanbul. The most significant is the Dolmabahçe Palace, constructed for Sultan Abdülmecit between 1843 and 1856.[210] It replaced the Topkapı Palace as the official imperial residence of the sultan.[211] The palace consists mainly of a single building with monumental proportions, which represented a radical rejection of traditional Ottoman palace design.[18] The style of the palace is fundamentally Neoclassical but is characterized by a highly eclectic decoration that mixes Baroque motifs with other styles.[212][213] Various new types of monuments were also introduced to Ottoman architecture during this era. For example, clock towers rose to prominence over the 19th century.[214][215] The construction of railway stations was a feature of Ottoman modernisation reflecting the new infrastructure changes within the empire. The most famous example is the Sirkeci Railway Station, built in 1888–1890 as the terminus of the Orient Express. It was designed in an Orientalist style by German architect August Jasmund (also spelled "Jachmund").[216] In the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul, Parisian-style shopping arcades appeared in the 19th century. Some consisted of a small courtyard filled with shops and surrounded by buildings, while others were simply a passage or alley (pasaj in Turkish) lined with shops, sometimes covered by a glass roof.[217] Other commercial building types that appeared in the late 19th century included hotels and banks.[218]

A local interpretation of Orientalist fashion steadily arose in the late 19th century, initially used by European architects such as Vallaury. This trend combined "neo-Ottoman" motifs with other motifs from wider Islamic architecture.[219][220] The eclecticism and European imports of the 19th century eventually led to the introduction of Art Nouveau, especially after the arrival of Raimondo D'Aronco in the late 19th century. D'Aronco came at the invitation of Sultan Abdülhamid II and served as chief court architect between 1896 and 1909.[221][222] Istanbul became a new center of Art Nouveau and a local flavour of the style developed.[223] The new style was most prevalent in the new apartment buildings being built in Istanbul at the time.[224]

The final period of architecture in the Ottoman Empire, developed after 1900 and in particular put into effect after the Young Turks took power in 1908–1909, is what was then called the "National Architectural Renaissance" and which gave rise to the style since referred to as the First national architectural movement of Turkish architecture.[225] The approach in this period was an Ottoman Revival style, a reaction to influences in the previous 200 years that had come to be considered "foreign", such as Baroque and Neoclassical architecture, and was intended to promote Ottoman patriotism and self-identity.[225] This was an entirely new style of architecture, related to earlier Ottoman architecture in rather the same manner was other roughly contemporaneous revivalist architectures related to their stylistic inspirations.[225] New government-run institutions that trained architects and engineers, established in the late 19th century and further centralized under the Young Turks, became instrumental in disseminating this "national style".[226]

Tile decoration[edit]

Early Ottoman tilework[edit]

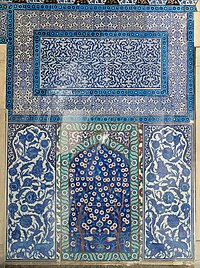

Some of the earliest known tile decoration in Ottoman architecture is found in the Green Mosque in Iznik, whose minaret incorporates glazed tiles forming patterns in the brickwork (although the current tiles are modern restorations). This technique was inherited from the earlier Seljuk period.[228] Glazed tile decoration in the cuerda seca technique was used in other early Ottoman monuments, particularly in the Green Mosque and the associated Green Tomb in Bursa.[229][230] The tiles of the Green Mosque complex generally have a deep green ground mixed with combinations of blue, white, and yellow forming arabesque motifs. A large portion of the tiles are cut into hexagonal and triangular shapes that were then fitted together to form murals.[231] Some of the tiles are further enhanced with arabesque motifs applied in gilt gold glazing over these colours.[18] Inscriptions in the mosque record that the decoration was completed in 1424 by Nakkaş Ali, a craftsman native to Bursa who had been transported to Samarkand by Timur after the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. In Samarkand, he was exposed to Timurid architecture and decoration and brought this artistic experience back with him later.[232][233] Other inscriptions record the tilemakers as being "Masters of Tabriz", suggesting that craftsmen of Iranian origin were involved. Tabriz was historically a major center of ceramic art in the Islamic world, and its artists appear to have emigrated and worked in many regions from Central Asia to Egypt.[234] The artistic style of these tiles – and of other Ottoman art – was influenced by an "International Timurid" taste that emerged from the intense artistic patronage of the Timurids, who controlled a large empire across the region.[233][235] Doğan Kuban argues that the decoration of the Green Mosque complex was more generally a product of collaboration between craftsmen of different regions, as this was the practice in Anatolian Islamic art and architecture during the preceding centuries.[236]

The same kind of tilework is found in the mihrab of the Murad II Mosque in Edirne, completed in 1435. However, this mosque also contains the first examples of a new technique and style of tiles with underglaze blue on a white background, with touches of turquoise. This technique is found on the tiles that cover the muqarnas hood of the mihrab and in the mural of hexagonal tiles along the lower walls of the prayer hall. The motifs on these tiles include lotuses and camellia-like flowers on spiral stems.[53] These chinoiserie-like motifs, along with the focus on blue and white colours, most likely reflect an influence from contemporary Chinese porcelain – although the evidence for Chinese porcelain reaching Edirne at this time is unclear.[53] Tilework panels with similar techniques and motifs are found in the courtyard of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, another building commissioned by Murad II in Edirne, completed in 1437.[237][238]

The evidence from this tilework in Bursa and Edirne indicates the existence of a group or a school of craftsmen, the "Masters of Tabriz", who worked for imperial workshops in the first half of the 15th century and were familiar with both cuerda seca and underglaze techniques.[239][240] As the Ottoman imperial court moved from Bursa to Edirne, they too moved with it. However, their work does not clearly appear anywhere after this period.[239] Later on, the Tiled Kiosk in Istanbul, completed in 1472 for Mehmed II's New Palace (Topkapı Palace), is notably decorated with Iranian-inspired banna'i tilework. The builders were likely of Iranian origin, as historical documents indicate the presence of tilecutters from Khorasan, but not much is known about them.[69] Another unique example of tile decoration in Istanbul around the same period is found on the Tomb of Mahmud Pasha, built in 1473 as part of the Mahmud Pasha Mosque complex. Its exterior is covered in a mosaic of turquoise and indigo tiles inset into the sandstone walls to form geometric star patterns. The work still reflects a traditional style of Anatolian or Persian tile decoration similar to older Timurid examples.[241][98]

Another stage in Ottoman tiles is evident in the surviving tiles of the Fatih Mosque (1463–70) and in the Selim I Mosque (1520–22). In these mosques the windows are topped by lunettes filled with cuerda seca tiles with motifs in green, turquoise, cobalt blue, and yellow.[229][242] Chinese motifs such as dragons and clouds also appear for the first time on similar tiles in Selim I's tomb, built behind his mosque in 1523.[229] A more extravagant example of this type of tilework can be found inside the tomb of Şehzade Mehmed in the cemetery of the Şehzade Mosque (1548).[243][244] Further examples can be found in a few religious structures designed by Sinan in this period, such as the Haseki Hürrem Complex (1539).[229][244] The latest example of it is in the Kara Ahmet Pasha Mosque (1555), once again in the lunettes above the windows of the courtyard.[229][243] Many scholars traditionally attribute these Ottoman tiles to craftsmen that Selim I brought back from Tabriz after his victory at the Battle of Chaldiran.[233][229][243] Doğan Kuban argues that this assumption is unnecessary if one considers the artistic continuity between these tiles and earlier Ottoman tiles as well as the fact that the Ottoman state had always employed craftsmen from different parts of the Islamic world.[229] John Carswell, a professor of Islamic art, states that the tiles are the work of an independent imperial workshop based in Istanbul that worked from Iranian traditions.[244] Godfrey Goodwin suggests that the style of tiles does not correspond to either the old "Masters of Tabriz" school or to an Iranian workshop, and therefore may represent an early phase of tilework from Iznik; an "early Iznik" style.[245]

An important case of Ottoman tile decoration outside the imperial capitals around this time was the refurbishment of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem ordered by Sultan Suleiman. During the refurbishment, the exterior of the building was covered in tilework which replaced the older Umayyad mosaic decoration.[246] Inscriptions in the tiles give the date 1545–46, but work probably continued until the end of Suleiman's reign (1566).[246] The name of one of the craftsmen is recorded as Abdallah of Tabriz. The tilework includes many different styles and techniques, including cuerda seca tiles, colourful underglaze tiles, and mosaic blue-and-white tilework. The tiles seem to have been fabricated locally rather than at centers like Iznik, despite the absence of a sophisticated ceramic production center in the region.[246] This project is also notable as one of the few cases of extensive tile decoration applied to the exterior of a building in Ottoman architecture. This major restoration work in Jerusalem may have also played a role in Ottoman patrons developing a taste for tiles, such as those made in Iznik (which was closer to the capital).[246][244]

Classical Iznik tiles[edit]

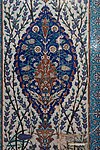

The city of Iznik had been a center of pottery production under the Ottomans since the 15th century, but until the mid-16th century it was mainly concerned with producing pottery vessels.[244][98] There is little evidence of large-scale tile manufacture in Iznik before this time.[233] In the late 15th century, in the 1470s or 1480s, the Iznik industry had grown in prominence and patronage and began producing a new "blue-and-white" fritware which adapted and incorporated Chinese motifs in its decoration.[247][248] Some of these blue-and-white ceramics appear in tile form in the decoration in the Hafsa Hatun Mosque (1522) in Manisa and in the Çoban Mustafa Pasha Mosque (1523) in Gebze.[97] The Hadim Ibrahim Pasha Mosque (1551) also contains panels of well-executed tiles featuring calligraphic and floral decoration in cobalt blue, white, olive green, turquoise, and pale manganese purple.[249] The most extraordinary tile panels from this period are a series of panels on the exterior of Circumcision Pavilion (Sünnet Odası) in Topkapı Palace. The tiles in this composition have been dated to various periods within the 16th century and some were probably moved here during a restoration of the pavilion in the first half of the 17th century. Nonetheless, at least some of the tiles are believed to date from the 1520s and feature large floral motifs in blue, white, and turquoise.[250][251] Both the Topkapı tiles and the mosque tiles from this early-16th-century period are traditionally attributed to Iznik, but they may have been produced in Istanbul itself in ceramic workshops located at Tekfursaray.[252][253][97] Even if they come from Tekfursaray, their style is related to the style of ceramics being made in Iznik around the same time.[254] This includes the saz style: a motif in which a variety of flowers are attached to gracefully curving stems with serrated leaves.[251][255] This continued to reflect earlier influences of the "International Timurid" style, but it also demonstrates the development of an increasingly distinct Ottoman artistic style at this time.[251]

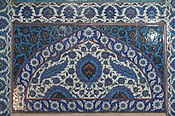

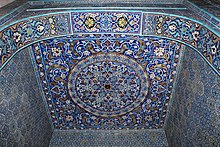

Ceramic art from Iznik reached its apogee in the second half of the 16th century, particularly with the advent of the "tomato red" colour in its compositions.[97][9] At the same time, Iznik grew into its role as a major center of tile production rather than just dishware.[256] Rather than merely highlighting certain architectural features (e.g. windows) with tile panels, large-scale murals of tilework became more common.[97] For this purpose, square tiles were also now preferred over the hexagonal tiles of the older Iranian tradition.[257] This was around the same time that Mimar Sinan, chief court architect, was also reaching the pinnacle of his career. Iznik ceramics and classical Ottoman architecture thus reached their greatest heights of achievement around the same time, during the reign of Suleiman and his immediate successors.[258] Sinan generally used tile decoration in a fairly restrained manner and seems to have preferred focusing on the architecture as a whole rather than on overwhelming decoration.[259][260] For example, Sinan's most celebrated works, the Süleymaniye Mosque (1550–57) and the Selimiye Mosque (1568-1574), feature tile decoration restricted to certain areas.[259] Even the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque (1568-1572), which is known for its extensive high-quality tile decoration, still concentrates and focuses this decoration onto the wall surrounding the mihrab instead of on the whole mosque interior.[261] The major exception to this is the Rüstem Pasha Mosque (1561–62), whose interior and outer portico are extensively covered in Iznik tiles.[97][260] The mosque is even regarded as a "museum" of Iznik tiles from this period.[261][9] Judging by comparisons with Sinan's other works, the exceptional use of tilework in this mosque may have been due to a specific request by the wealthy patron, Rüstem Pasha, rather than a voluntary decision by Sinan himself.[97] There is no evidence that Sinan was closely involved in the production of tiles and it's likely that he merely decided where tile decoration would be placed and made sure that the craftsmen were capable.[262] Doğan Kuban also argues that while the vivid tiles inside the mihrab of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque could have symbolized an image of Paradise, tile decoration in Ottoman mosques did not generally have deeper symbolic meanings.[259] Moroever, unlike Byzantine mosaics, tiles were also not well-suited to curved surfaces and as a result they were not used to decorate domes, which were decorated with painted motifs instead.[261]

The tilework in Rüstem Pasha Mosque also marks the beginning of the artistic peak of Iznik tile art from the 1560s onward.[9] Blue colours predominate, but the important "tomato red" colour began to make an appearance. The repertoire of motifs includes tulips, hyacinths, carnations, roses, pomegranates, artichoke leaves, narcissus, and Chinese "cloud" motifs.[9][261] Around 1560 the colour palette of Iznik tiles also shifted slightly. With the introduction of tomato red, which was perfected in the following years, some colours like turquoise and manganese purple stopped appearing, while a new shade of green also appeared. This shift is partly evident in the Rüstem Pasha Mosque and especially in the extensive tilework in the tomb of Haseki Hürrem (1558) and the tomb of Suleiman (1566), both located behind the Süleymaniye Mosque.[263] The highest artistic form of Iznik tiles was achieved soon after this during the reign of Selim II, who succeeded his father Suleiman, and continued until the end of the century. Some of the most exceptional tilework examples from this period can be found in the Sokullu Mehmed Pasha Mosque, the Piyale Pasha Mosque (1574), the tomb of Selim II (1576), the small Takkeci İbrahim Ağa Mosque (1592), the tomb of Murad III (1595), and in some parts of the Topkapı Palace.[264] The tilework panels in the Chamber of Murad III (1578) in Topkapı Palace and in the mihrab area of the Atik Valide Mosque (1583) in Üsküdar also show a trend of using colours in more abstract ways, such as the adding of red spots on flower petals of different colours, which is a detail particular to Ottoman art.[262] As noted by Arthur Lane in his seminal study of Iznik tiles published in 1957, the effect of Iznik tilework, when successfully employed in Ottoman domed interiors, results in a feeling of lightness and harmony, where the intricate details of the tiles themselves do not overwhelm the onlooker.[262] Tile decoration in the provinces was typically of lesser quality to that found in the main imperial centers of patronage. However some wealthy local patrons probably imported tiles from Istanbul, which explains the high-quality tilework in some distant monuments such as the Behram Pasha Mosque (1572–73) in Diyarbakir.[261]

- Iznik tilework in the second half of the 16th century

-

Tiles in the Tomb of Roxelana, Istanbul (1558)

-

Tiles in the mihrab of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, Istanbul (circa 1561)

-

Tiles in the outer portico of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, Istanbul (circa 1561)

-

TIles in the Mausoleum of Suleiman, Istanbul (1566)

-

Tile decoration in the Sokullu Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Istanbul (1572)

-

Detail of tiles in the Sokullu Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Istanbul (1572)

-

Tilework near the mihrab in the Selimiye Mosque, Edirne (circa 1574)

-

Detail of tiles in the Selimiye Mosque, Edirne (circa 1574)

-

Detail of tiles in the Selimiye Mosque, Edirne (circa 1574)

-

Tile panel at the entrance to the Tomb of Selim II in Istanbul (1576)

-

Tiles in the Atik Valide Mosque, Istanbul (1583)

In the early 17th century, some features of 16th-century Iznik tiles began to fade, such as the use of embossed tomato red. At the same time, some motifs became more rigidly geometric and stylized.[262] The enormous Sultan Ahmed Mosque (or "Blue Mosque"), begun in 1609 and inaugurated in 1617, contains the richest collection of tilework of any Ottoman mosque. According to official Ottoman documents it contained as many as 20,000 tiles.[262] The dominant colours are blue and green, while the motifs are typical of the 17th century: tulips, carnations, cypresses, roses, vines, flower vases, and Chinese cloud motifs.[265] The best tiles in the mosque, located on the back wall on the balcony level, were originally made for the Topkapı Palace in the late 16th century and were reused here.[145] The massive undertaking of decorating such a large building strained the tile industry in Iznik and some of the tilework is repetitive and inconsistent in its quality.[266] The much smaller Çinili ("Tiled") Mosque (1640) in Üsküdar is also covered in tilework on the inside.[267] The most harmonious examples of tile decoration in 17th-century Ottoman architecture are the Yerevan Kiosk and Baghdad Kiosk in Topkapı Palace, built in 1635 and 1639, respectively.[268][145] Both their exterior and interior walls are covered in tiles. Some of the tiles are cuerda seca tiles of a much earlier period, reused from elsewhere, but most are blue-and-white tiles that imitate early 16th-century Iznik work.[145]

While the craftsmen at Iznik were still capable of producing rich and colourful tiles throughout the 17th century, there was an overall decline in quality. This was a result of a decline in imperial commissions, as fewer major building projects were sponsored by ruling elites during this period.[269] The Celali revolts in the early 17th century also had a significant impact, as Evliya Çelebi records that the number of tile workshops in Iznik during this time dropped from 900 to only 9.[267] Some of the production continued in the city of Kütahya instead of Iznik.[267] Kütahya, unlike Iznik, had not become solely reliant on imperial commissions and as a result it weathered the changes more successfully. Many of its artisans were Armenians who continued to produce tiles for churches and other buildings.[270]

Tile manufacture declined further in the second half of the century.[267] Nonetheless, the interior of the "New Mosque" or Yeni Cami in the Eminönü neighbourhood, completed in 1663, is a late example of lavish Iznik tile decoration in an imperial mosque. The finest tiles in the complex are reserved for the sultan's private gallery and lounge (the Hünkâr Kasrı).[271] By this period, blue and turquoise colours increasingly predominated, and many commissioned works limited their patterns to single tiles instead of creating larger patterns across multiple tiles.[269] Tiles like this were imported in significant quantities to Egypt around this time, as can be seen in the Aqsunqur Mosque (otherwise known as the "Blue Mosque") in Cairo, which was renovated in 1652 by Ibrahim Agha, a local Janissary commander.[272][273]

- Iznik tiles in the 17th century

-

Tiles (with painted decoration above) on the back wall of the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, Istanbul (circa 1617)

-

Detail of tiles in the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, Istanbul (circa 1617)

-

Tiled interior of the Baghdad Kiosk in Topkapı Palace (1639)

-

Tiled mihrab of the Çinili Mosque (1640)

-

Iznik tiles in the Aqsunqur Mosque in Cairo, Egypt (1652)

-

The tiled interior of the Hünkâr Kasrı (sultan's pavilion) at the New Mosque, Istanbul (circa 1663)

Tekfursaray and Kütahya tiles (18th century)[edit]

Tile production in Iznik came to an end in the 18th century.[267] Ahmet III and his grand vizier attempted to revive the tile industry by establishing a new workshop between 1719 and 1724 at Tekfursaray in Istanbul, where a previous workshop had existed in the early 16th century.[274][275] Production continued here for a while but the tiles from this period are not comparable to earlier Iznik tiles.[274][267] Pottery production also continued and even increased at Kütahya, where new styles developed alongside imitations of older classical Ottoman designs.[276][275] The colours of tiles in this period were mostly turquoise and dark cobalt blue, while a brownish-red, yellow, and a deep green also appearing. The background was often discoloured, colours often ran together slightly, and the patterns were again typically limited to single tiles.[274][275] The earliest recorded Tekfursaray tiles are those made in 1724–1725 for the mihrab of the older Cezeri Kasım Pasha Mosque (1515) in Eyüp, Istanbul.[275][277] Tekfursaray tiles are also found in the Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque (1734), on the Ahmed III Fountain (1729) near Hagia Sophia, and in some of the rooms and corridors of the Harem section in Topkapı Palace.[274] Kütahya tiles are present in Istanbul in the Yeni Valide Mosque in Üsküdar (1708–1711), the Beylerbeyi Mosque (1777–1778), and arts of Topkapı Palace, and well as in mosques in other cities like Konya and Antalya.[275]

The Kütahya and Tekfursary kilns notably produced a number of tiles and groups of tiles that were painted with illustrations of the Great Mosque of Mecca. These appear in multiple buildings the 18th century, but some examples of this appeared even earlier in Iznik tiles from the late 17th century.[278] Earlier examples show the Kaaba and the surrounding colonnades of the mosque in a more abstract style. Later examples in the 18th century, influenced by European art, employ perspective in depicting the mosque and they sometimes depict the entire city of Mecca.[275] Depictions of Medina and the Prophet's Mosque also appear in other specimens of the time. Examples of these pictorial tile paintings can be seen in the collections of several museums as well as inside some mosques (e.g. the Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque) and in several rooms at Topkapı Palace, such as the tiles adorning the mihrab of the prayer room of the Black Eunuchs.[278]

After the Patrona Halil rebellion in 1730, which deposed Ahmet III and executed his grand vizier, the Tekfursaray kilns were left without a patron and quickly ceased to function.[275] The shortage of quality tiles in the 18th century also caused Iznik tiles from older buildings to be reused and moved to new ones on multiple occasions.[274] For example, when repairs were being done at Topkapı Palace in 1738 old tiles had to be removed from the Edirne Palace and shipped to Istanbul instead.[275] Ultimately, tilework decoration in Ottoman architecture lost its significance during the 18th century.[267] Kütahya nonetheless did continue to produce decorative tiles up to the 19th century, though the quality deteriorated in the late 18th century.[279] Some of the potters in the city were Armenian Christians and some of the tiles were commissioned for Armenian churches. Christian tile decoration of this period often depicted saints, angels, the Virgin Mary, and biblical scenes. Examples can be found at the Krikor Lusaroviç Church in Tophane, Istanbul, and the Surp Astvazazin Church in Ankara, among others. Some of the tiles were exported further abroad and examples of them have been found in Jerusalem, Cairo, and Venice.[280] A moderately successful effort to revive Ottoman tile production occurred under Abdülhamid II in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, partly under the influence of the First National Architectural Movement. This period saw tiles produced for several new mosques, schools, and government buildings. These workshops eventually closed down after the First World War.[281]

Paradise garden[edit]

"The semblance of Paradise (cennet) promised the pious and devout [is that of a garden] with streams of water that will not go rank, and rivers of milk whose taste will not undergo a change, and rivers of wine delectable to drinkers, and streams of purified honey, and fruits of every kind in them, and forgiveness from their lord".(47:15)[282]

According to the Qur'an, paradise is described as a place, a final destination. Basically the eternal life, that is filled with "spiritual and physical" happiness.[283] Earth gardens in the Ottoman period were highly impacted by paradise, therefore connected with the arts and spaces of everyday life, having many descriptions relating to the Qur'an.[284] Hence, paradise gardens, or "Earthly Paradise",[285] are abstract perceptions of heaven, as a result must symbolize a serene place that shows "eternity and peace".[286]

Nature became a method for decorative patterns in architectural details and urban structure. Everything was inspired by nature and became included with nature. From the ceilings of the mosques and the walls of the palaces, kiosks and summer palaces (pavilions), which were all embellished with tiles, frescoes and hand-carved ornaments, to the kaftans, the yashmaks and so much more. Clearly, paradise's nature was everywhere; in many spaces of daily life.[287]

Without a doubt, the general layout of the gardens did reflect many descriptions in the Qur'an, yet one of the great strengths of early Islam, was that Muslims looked at different sources and used useful ideas and techniques from diverse sources, particularly Byzantium (the Eastern Roman Empire).[288] Garden pavilions often took the form of a square or centrally planned free-standing structures open on all sides, designed specifically to enjoy the sight, scent and music of the environment.[289] Some of the forms of the gardens were based for instance on the Hagia Sophia's atrium, which has cypresses around a central fountain, and the plantings in the mosques were given a "specifically Muslim theological interpretation". The mosques expanded its functions and services, by adding hospitals, madars, libraries, etc., and therefore gardens helped organize the elements for all the various buildings.[290]

In Islamic cities, such as the Ottoman cities, where the mosques were considered as the "focal" point,[291] it was common for mosques to have adjacent gardens.[290] Therefore, mosque structures were based somewhat to relate to the gardens. For example, the Süleymaniye Mosque had windows in the qibla wall to create continuity with the garden outside. The mihrab had stained glass windows and Iznik tiles that suggest a gate into paradise. The windows looking outwards to the garden to create the effect in which flowers from the garden act as if it would "perfume the minds of the congregation as if they have entered heaven." Also, Rüstem Pasha mosque was known for its usage of Izink tiles, where the decoration design provides a showcase for the Iznik tile industry. The inscriptions on pendentives suggest that the soul of the devout is certain to reside in paradise.[292] The main inscriptions in these mosques were of water and ponds, kiosks, fruits such as pomegranates, apples, pears, grapes, etc. Also wine, dance, music, serving women and boys, all which turn the entertainment vision into a "paradise on earth".[293]